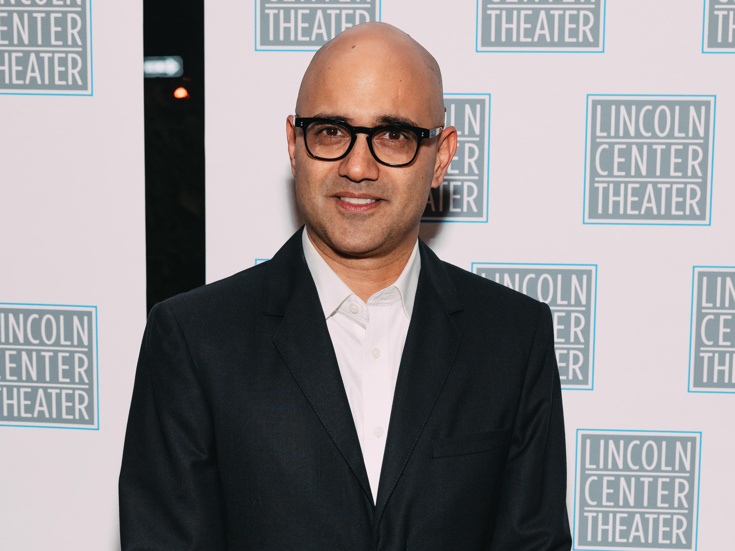

Playwright Ayad Akhtar on Blending Literature, Technology and the Star Power of Robert Downey Jr. in McNEAL

(Photo by Emilio Madrid for Broadway.com)

What do you get when you toss Hedda Gabler, King Lear, Madame Bovary and many other works of world literature into a chatbot? Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Ayad Akhtar imagines the result in his ingenious new play McNEAL. Oscar winner Robert Downey Jr. makes a magnetic Broadway debut as the title novelist, a hard-drinking narcissist who manages to alienate almost everyone he encounters while dabbling in AI technology to compose his next work of fiction.

It’s the most audacious play yet from Akhtar, who previously examined the complications of being a Muslim in America in Disgraced and The Who & the What, as well as in his acclaimed novels Homeland Elegies and American Dervish. For McNEAL, director Bartlett Sher turns Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont Theater into a sleek, futuristic space for Downey and a supporting cast that includes Tony winners Andrea Martin and Ruthie Ann Miles. In conversation, Akhtar is friendly and direct, revealing a few of his fast-moving play’s literary Easter eggs and explaining why he could never choose between writing drama and fiction.

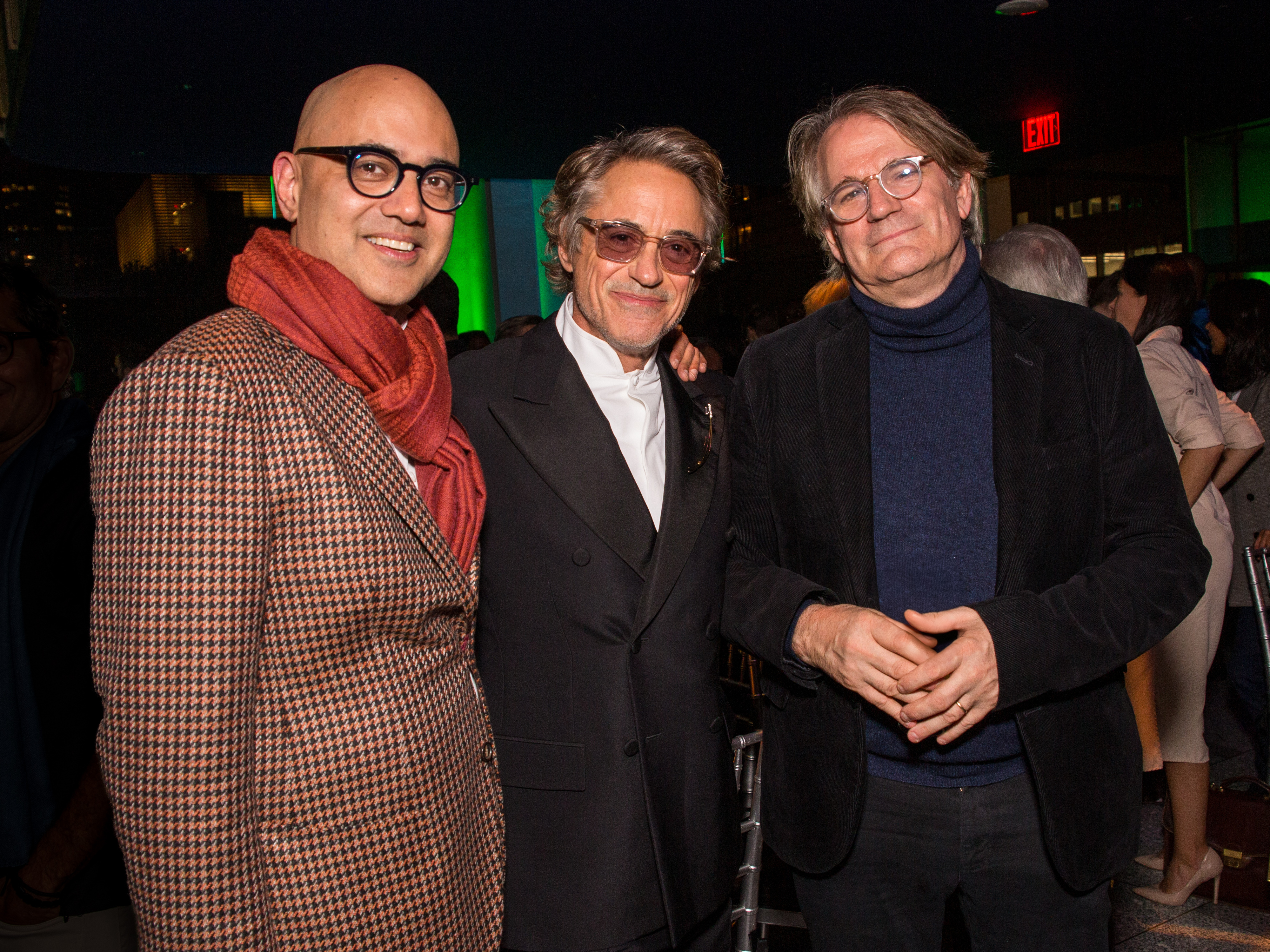

(Photo: Tricia Baron)

Tell us about your inspiration for this play and the character of Jacob McNeal. Is he a tragic Shakespearean figure?

The play is telling the story of the writing of the play. Texts get uploaded into the Chat bot—King Lear, Hedda Gabler, Madame Bovary, Oedipus, the [Biblical] parable of the Prodigal Son—and what happens over the course of the play is endless variations on what’s uploaded. Hedda Gabler is, of course, a play in which a woman who might be insane or just divinely inspired burns a manuscript and shoots herself. Guess what? We have a manuscript that gets burned and a woman who shoots herself. So the process of watching the play is disorienting, because on the one hand it’s telling the linear story of a character, “Jacob McNeal,” who is sometimes “himself” because he, too, is a kind of composite figure comprised of all the influences in the play.

Fascinating—I picked up on some of those references while watching the play but not others.

It’s one of the things about the play that has been elusive to anybody wanting to comment on it, which is unfortunate, because a lot of people have decided to comment on a play I didn’t write.

You’ve never seemed concerned about making the characters in your plays likeable—there’s even a line in McNEAL about literature not being about liking the people in it.

But isn’t it hard not to like Robert? I feel like he takes care of a lot of that for me.

How does his performance fulfill your vision?

It heightens it. It expands it. The play is more playful, wilder and bolder with him in it. It’s more entertaining. It’s just a richer play, full of his life and his inspiration. I’ve often said that he is the soul of the play. Robert is a sublime artist.

McNEAL is your first star vehicle. Had you been thinking about writing a big part for a big star?

Not exactly. This is my third outing on Broadway, and one thing I’ve noticed is that in large houses, when you have a single lead character, the audience can much more clearly understand how to manage the story. With a story this complex and rich with philosophical and intellectual implications, it felt important to tether it with one presence. Having written my first draft, I thought, “This is a part that a star would want to play.”

How did you become interested in AI technology?

It just happened naturally when, in November 2022, ChatGPT dropped and everyone started experimenting with it; kids were using it for assignments. It caught my interest because it was what was happening in the world.

How did it affect your writing of this play?

A lot of stuff in the play is inspired by ideas I had working with the technology. Any good story is an imitation of life, and this play is staging the facsimile of a writer using AI to write a play. Unfortunately, I was not able to use the technology myself because it wasn’t good enough to do what I wanted. But I set the play in “the very near future” when it would be good enough to do that.

I can’t imagine AI being able to produce the level of dialogue that you write.

Maybe not, but it’s already to the point where it can get pretty close.

There’s a throwaway line at the beginning of the play about the bestseller list having three books on it created by AI. Should we shrug at that idea?

I don’t think we should shrug, but I also don’t think we should pretend it’s not possible in the near future. Honestly, it doesn’t matter what I think [about AI], it’s already happening. The larger question is not moralizing about it, it’s understanding that this technology is taking over the world.

You’ve used your life and your family history in your writing, as Jacob McNeal does. Are you addressing that indirectly in the play?

Most writers do that, even if they don’t admit it. It’s got to come from somewhere that feels true. The play is about the creative act, about creative inspiration, about where creativity comes from—it’s questioning all of that. A lot of the play was inspired by literary figures I admire, particularly Saul Bellow, who was probably the most important American writer for me coming of age. The fact that nobody reads Bellow anymore is unfathomable. Before every book he wrote came out, his lawyers and agents were terrified they would get inundated with lawsuits. All the people in his life recognized themselves in his books. That’s just what we do as writers—some, like Bellow, with less shame; others of us hide the process as much as possible.

(Photo: Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman)

If you could only do one kind of writing, what would you choose?

I don’t think I could write just one kind of thing. I always say that the thing I love about fiction is that I get to do it by myself, but that’s what I hate about it, too. And the thing I love about writing for the theater is that I get to do it with other people, but that’s what I hate about it, too. When I get enough solitude, I realize I need community, and when I get enough community, I realize I need my solitude.

To oversimplify, when you write plays, you must feel, “Somebody’s got to get up and say this.”

I think that’s true. There’s something about language in the public space and the way it builds community—in the process of entertaining, it makes people reflect on what’s going on and what matters. The playwrights I admire most are the ones who not only have written about eternal human struggles, but they also have done so in ways that resonate with their contemporary audiences. Shakespeare is, of course, primary in that respect. It’s amazing how much those plays are really just him commenting on his cultural moment. The plays that we think are about the eternal human condition are also about the politics of their era. They were deeply in dialogue with events happening on the street, ripped from the headlines.

"When I get enough solitude, I realize I need community, and when I get enough community, I realize I need my solitude."

–Ayad Akhtar

Who are your favorite contemporary playwrights?

You will never get me to speak about my competitors.

Well, they’re not competitors, they’re contemporaries.

We’re all competitors with each other. And I mean that with respect. I learn from my compadres, I’m going to their work and I’m learning what I can, but I’m not going to comment on them.

You don’t feel like you’re part of the theatrical community and can say “I love Annie Baker” or Amy Herzog or whoever?

I am certainly part of the theatrical community, and I have admiration for so many of my colleagues, but I never have spoken about any of them.

Are you still working on a musical version of La La Land? What’s the status of that?

Yes, Bart Sher and I are doing it together. [Akhtar is writing the book with Matthew Decker; the score is by Justin Hurwitz, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul.] We’ve got a workshop next week. I can’t [comment on casting] because at this moment, I don’t know—there are some musical chairs happening. It’s my first time, and I’m enjoying the experience of getting to listen to music for so much of the rehearsal day. It’s a different storytelling muscle because the book is about getting you to high dramatic moments that are expressed through music, but yeah, I’ve been having a good time.

Your plays have been produced in small theaters downtown and in the big, beautiful Beaumont. What do you enjoy about Broadway?

As a writer on Broadway, you’re part of the national conversation. When there’s a show like this at the Beaumont, you have people coming to see it from all over the world. There are aesthetic challenges and certain expectations about what Broadway has become, but you’re in dialogue with different kinds of people across the globe. That, to me, is thrilling.

(Photo: Ilya S. Savenok for Getty Images)